When Bruce Springsteen first sang “Born to Run,” he captured the restless fire of youth — a heart racing against the horizon, desperate for something more. Decades later, that same spirit of longing was supposed to pulse through Deliver Me From Nowhere, the new biopic inspired by Nebraska, Springsteen’s most haunting and introspective album. But instead of running wild, it seems this movie barely walks.

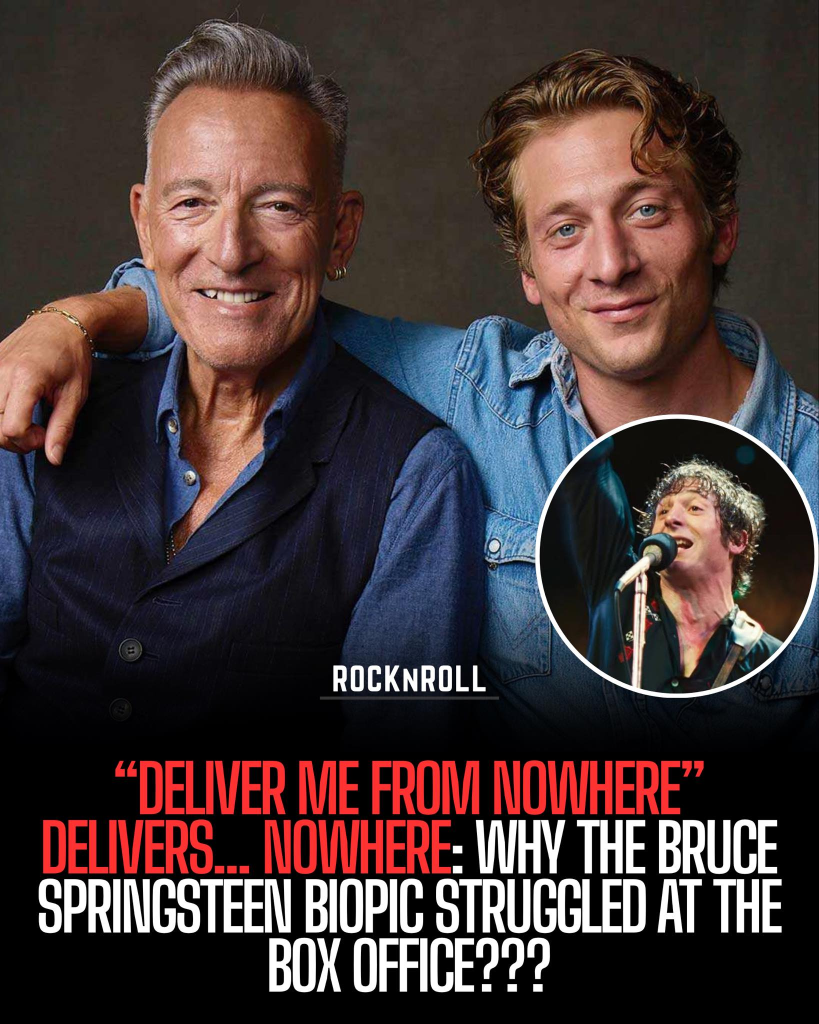

Directed by Scott Cooper and starring Emmy-winner Jeremy Allen White as a young, conflicted Springsteen, Deliver Me From Nowhere was billed as a revelation — a rare cinematic glimpse behind the myth of “The Boss.” On paper, it had everything: an acclaimed filmmaker known for gritty realism (Crazy Heart, Out of the Furnace), a hot young actor riding the wave of prestige television, and one of the most revered figures in American music. It was supposed to be a thunder road of emotion. But somewhere between artistic reverence and cinematic rhythm, the film lost its drive.

A PROMISE WRAPPED IN DARKNESS

From the very first announcement, Deliver Me From Nowhere carried an air of solemn importance. It wasn’t meant to be another cradle-to-stage rock biopic filled with neon lights and stadium cheers. Instead, it focused on the lonely months of 1982 when Bruce Springsteen, at the peak of his fame, disappeared into his bedroom studio to record Nebraska — a stripped-down collection of songs about isolation, guilt, and the American dream gone cold.

That concept alone should’ve made the film electric — a deep dive into the psychology of an artist who traded the roar of crowds for the whisper of a tape recorder. But Cooper’s direction leans so hard into that silence that the film almost forgets to breathe. Long shots of Jeremy Allen White brooding in dimly lit rooms become the visual motif, his face half-shadowed, his voice barely above a whisper.

The problem isn’t the stillness — it’s the stagnation. The film’s reverence for its subject matter becomes its own cage. Every frame aches with sincerity, but it rarely burns with vitality.

JEREMY ALLEN WHITE: A PERFORMANCE TRAPPED IN THE QUIET

Jeremy Allen White delivers what might be the most studied portrayal of Springsteen ever attempted on screen. He doesn’t mimic the voice or swagger — he internalizes the burden. His performance is tight, coiled, and thoughtful, capturing the tension of a man torn between fame and authenticity. There are moments, fleeting but powerful, when he seems to embody that familiar contradiction: a rock god afraid of his own reflection.

But the film gives him too little to play with. The script, adapted from Warren Zanes’ acclaimed book, becomes a loop of introspection — a man sitting alone, haunted by America, faith, and his father’s ghost. There are rare flashes of fire — a frustrated jam session, a quiet confession to bandmate Steven Van Zandt (played with warmth by Scoot McNairy) — but they flicker and vanish like static on an old tape.

White’s eyes say everything, but the film never lets him speak. And that’s both its poetry and its downfall.

TOO MUCH LIKE NEBRASKA — AND NOT ENOUGH LIKE BRUCE

Critics have been quick to point out the irony: Deliver Me From Nowhere feels too much like the album it celebrates. It’s sparse, minimalist, and deeply melancholic. But where Nebraska transformed stillness into transcendence — its silence loaded with heartbreak and grace — the film’s quiet feels heavy, almost oppressive.

Springsteen’s music, even in its darkest moments, always found the human pulse beneath despair. There’s rhythm in his melancholy, movement in his pain. Cooper’s film, for all its reverence, seems to forget that.

It’s a movie that honors the myth of Bruce Springsteen but misses the music of him.

Even the score — an ambient reinterpretation of Nebraska’s songs — floats like ghostly echoes rather than driving the story forward. When “Atlantic City” finally plays, it lands less like revelation and more like resignation.

A FILM FOR FANS, NOT THE FAITHFUL

There’s a certain bravery in refusing to make Bohemian Rhapsody 2.0. Deliver Me From Nowhere doesn’t chase commercial triumph — it chases truth, or at least what it thinks truth looks like. For die-hard fans of Springsteen, that authenticity may feel like a holy offering: a chance to witness his creative torment up close, the sleepless nights and inner storms that birthed one of his most misunderstood albums.

But for casual viewers — or anyone expecting even a trace of The Boss’s fire — the film may feel like a slow march through fog.

The pacing borders on glacial. The dialogue, intentionally muted, often feels adrift in its own seriousness. Even when Springsteen finally records “Reason to Believe,” one of Nebraska’s rare hopeful moments, the scene lands without catharsis. It’s art trapped in amber — beautiful, but frozen.

SCOTT COOPER’S ARTISTIC GAMBLE

Scott Cooper has built a career on quiet desperation — men at the edge of themselves, scraping for meaning. Deliver Me From Nowhere fits that mold perfectly, maybe too perfectly. You can feel Cooper’s respect for Springsteen in every frame; the film is practically a hymn. But devotion can be dangerous.

By idolizing its subject, the movie forgets to dramatize him.

Instead of a beating heart, we get a museum piece — lovingly curated, meticulously crafted, but behind glass. Cooper’s earthy cinematography captures the grit of small-town New Jersey and the ghostly glow of the recording room, yet it all feels emotionally airless. You admire it, but you rarely feel it.

THE SOUND OF SILENCE

There’s a scene midway through the film that encapsulates everything good — and frustrating — about Deliver Me From Nowhere. Springsteen sits alone in his car, engine off, listening to a cassette of his unfinished demo. Rain falls. His reflection stares back from the windshield. He mutters softly, “It’s too much truth.”

It’s devastating, subtle, and perfectly in tune with Nebraska’s spirit. But like the rest of the film, it ends just as it’s about to break open. The emotion is there, trembling under the surface, but it never quite finds release.

What’s missing isn’t effort — it’s electricity.

BETWEEN THE LYRICS AND THE LEGEND

There’s no denying the film’s ambition. It dares to tackle an era most filmmakers would avoid: a time when Bruce Springsteen wasn’t conquering the world but questioning whether he still wanted to. It’s a story about artistic doubt, emotional exile, and the cost of authenticity — themes that feel painfully relevant in today’s age of overexposure and performance.

Yet in choosing reverence over revelation, Deliver Me From Nowhere ends up feeling less like a confession and more like a eulogy.

Springsteen’s music — even his darkest — always had one eye on redemption. Cooper’s film, for all its artistry, seems stuck in the shadows.

THE VERDICT: BEAUTIFUL, BLEAK, AND BEGGING FOR LIFE

In the end, Deliver Me From Nowhere is both exactly what it set out to be and less than what it could have been. It’s a film that worships the artist but forgets the audience — a poetic slow burn that risks burning out entirely.

Jeremy Allen White gives the kind of performance that will be studied for its nuance, even if few will revisit the movie itself. The cinematography glows like memory. The intent is noble. But intent isn’t enough.

As one critic wrote, “It’s a film that honors the music, but forgets the magic.”

Maybe that’s the point. Maybe Deliver Me From Nowhere was never meant to run — only to wander. To linger in the lonely spaces between fame and faith, melody and silence.

And maybe, somewhere, Bruce Springsteen would smile at that. Because for all its flaws, it still dares to look where few artists — and fewer films — ever do: into the quiet, unforgiving heart of truth itself.