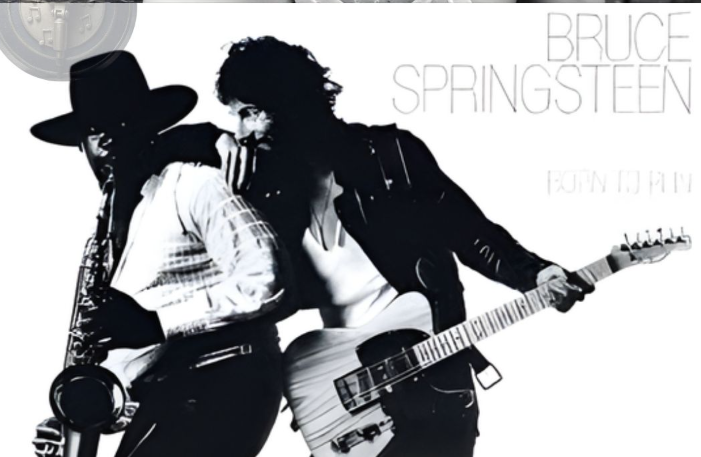

When Bruce Springsteen released Born to Run in 1975, America heard escape at full volume. The opening swell—engines revving, drums charging forward, guitars bursting like headlights on a dark highway—felt like liberation itself. It sounded like motion, like promise, like the kind of freedom that could only be found by leaving everything behind. For millions, the song became an anthem of youth and possibility, a declaration that the road still led somewhere better.

But beneath the roar, something quieter—and far more unsettling—was already happening.

Born to Run was not simply about chasing a dream. It was about sensing, early and instinctively, that the dream was shrinking. That the clock was speeding up. That the systems meant to reward effort and loyalty were beginning to close their doors. What sounded like hope was also an alarm.

Springsteen has always insisted that his characters are not reckless romantics. They are observers. Survivors. People who can feel the walls moving inward long before the rest of the world notices.

And that is what makes Born to Run endure—not as nostalgia, but as prophecy.

The Sound of Escape—and the Fear Behind It

On the surface, Born to Run feels cinematic and triumphant. Wendy and the narrator are poised to break free from a town that can’t hold them, racing toward something larger than themselves. The music doesn’t linger; it surges forward, breathless, urgent, as if stopping would be fatal.

But urgency is not the same as optimism.

Urgency is what you feel when time is running out.

Springsteen wrote the song in a moment when the postwar American promise was already cracking. The factories that had once guaranteed steady work were beginning to falter. Towns built around a single industry were becoming fragile. Young people could sense that the ladder their parents climbed was wobbling—and in some places, disappearing entirely.

So they didn’t stroll toward the future.

They ran.

Running From, Not Just To

One of the most misunderstood elements of Born to Run is the idea of escape. Popular culture often frames the song as a joyful rebellion against small-town boredom. But Springsteen’s escape is not carefree—it is necessary.

“These towns rip the bones from your back,” he sings.

That line is not metaphorical bravado. It is exhaustion. It is the feeling of being drained by work that leads nowhere, by loyalty that is never returned, by systems that take more than they give. The town is not evil—but it is consuming.

The characters in Born to Run aren’t chasing excess or fantasy. They are trying to preserve themselves before something essential is lost: time, dignity, belief.

This is not about youth wanting more.

It is about youth realizing they are being offered less.

The American Dream, Already Receding

By the mid-1970s, the American Dream was still being sold—but fewer people were buying it without question. Wages stagnated. Manufacturing declined. Inflation rose. Trust in institutions weakened. Vietnam, Watergate, and economic instability had left a generation skeptical of promises wrapped in slogans.

Springsteen didn’t write Born to Run as a political statement. He wrote it as a human one.

His characters understand—perhaps only subconsciously—that staying put may mean surrender. That working hard might no longer be enough. That the rules are changing, but no one has explained the new ones.

So they gamble on motion.

The road becomes not a symbol of adventure, but of survival.

The Weightiest Lyric

Years later, Springsteen would reflect on which line in Born to Run carried the most weight. It wasn’t the romantic imagery. It wasn’t the highway poetry.

It was this:

“Tramps like us, baby we were born to run.”

The word tramps matters.

These are not heroes or chosen ones. They are disposable in the eyes of the system. Drifters not by choice, but by circumstance. People who sense they may never fully belong to the future being promised to them.

To be “born to run” is not to be born free.

It is to be born with no margin for standing still.

That lyric reveals the song’s quiet grief: if you don’t keep moving, you will be left behind.

Romance as Armor

The love story at the center of Born to Run is real—but it is also protective. Wendy isn’t just a partner; she is proof that something human can still be carried forward. Love becomes the last stable thing when work, place, and identity feel unstable.

Springsteen understood that romance often blooms brightest in moments of pressure. When everything else feels uncertain, connection becomes the thing worth risking everything for.

The tenderness in the song—the promises, the whispered hopes—is not naïve. It is defiant. It is two people refusing to let the world flatten them into resignation.

But even that tenderness is urgent.

Because they know they may not have much time.

The Anxiety Beneath the Anthem

Listen closely, and Born to Run is restless. The rhythm barely pauses. The melody strains upward, as if reaching for something just out of grasp. There is joy—but it is edged with panic.

This is not the sound of arrival.

It is the sound of acceleration.

Springsteen packed the song so tightly because he knew the feeling he was chasing: that moment when you realize the future is no longer guaranteed, and every choice suddenly feels heavier. When staying feels dangerous. When leaving feels like the only remaining act of agency.

That anxiety—the sense that something precious is slipping away even as you race forward—is the emotional engine of the song.

Why the Song Feels Like Prophecy Now

Decades later, Born to Run feels less like a time capsule and more like a mirror. The conditions Springsteen hinted at—precarious work, shrinking opportunity, the pressure to move constantly just to stay afloat—have only intensified.

Today’s young people run too.

They run between gigs, cities, debts, expectations. They chase stability that keeps retreating. They sense, as Springsteen’s characters did, that standing still is not an option the system allows.

That is why the song still lands so hard.

It wasn’t about one generation’s escape.

It was about the beginning of a long pattern.

Hope, But Not Comfort

Born to Run does contain hope—but it is not comforting hope. It is muscular, risky, earned hope. Hope that demands motion, courage, and sacrifice.

Springsteen never promised that the road would lead to paradise. Only that it was better than surrender.

And that distinction matters.

The song doesn’t say the dream is dead.

It says it is harder to reach—and easier to lose.

What Was Already Being Lost

What Born to Run captured—quietly, almost accidentally—was the first widespread feeling that the American Dream might no longer be durable. That it might not survive without constant motion. That it might belong only to those willing to outrun its collapse.

The fire, the romance, the sound of freedom—those were real.

But so was the fear.

And that is why the song endures.

Not because it reminds us of who we were—but because it warned us, early on, about what we were beginning to lose.

Born to Run didn’t just soundtrack an escape.

It documented the moment a generation realized escape might be necessary at all.