Country superstar Luke Bryan has always been known for his affable personality, down-to-earth interviews, and family-first image. So when news broke that he went public with an unexpectedly hardline response to a bullying incident involving his child, fans were taken aback — and the debate exploded.

According to the account that circulated after the incident, a son or daughter of Bryan returned home from school with a visible forehead injury. The child’s parents believed the mark resulted from a bullying episode. In a clear break from his usual good-guy persona, the singer allegedly announced an uncompromising stance: if his child had warned another child to stop and that child persisted, his child had been told to defend themselves physically — even if that meant throwing a punch.

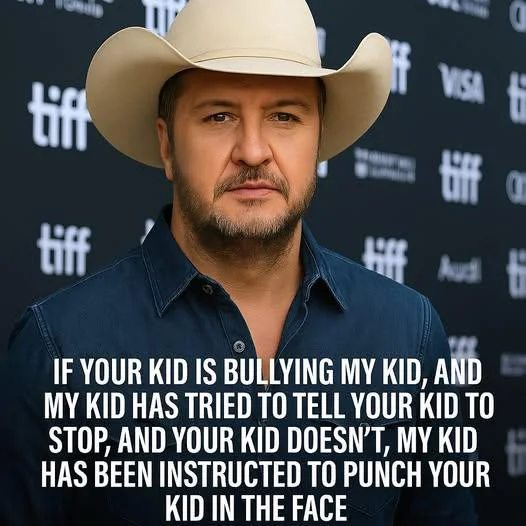

“If your kid is bullying my kid, and my kid has tried to tell your kid to stop, and your kid doesn’t, my kid has been instructed to punch your kid in the face,” the quote read, expressed with the kind of bluntness that immediately put a spotlight on the issue of parental responses to bullying.

That declarative statement has set off an intense conversation about parenting, the emotional aftermath of bullying, legal consequences, and whether solution-oriented alternatives exist. Fans and commentators are divided: some applaud the fatherly protectiveness and tough-love stance; others worry that encouraging violence normalizes harm and could make a bad situation worse.

Below, we unpack the incident, explore why it struck such a nerve, and review the complexities every parent should consider when protecting a child who’s been bullied.

What reportedly happened

Per the reports circulating after the incident, Bryan’s child came home with a forehead injury that the family believed was caused by an altercation at school. The child apparently told parents they had asked the aggressor to stop, but the behavior continued. Hurt, frightened, and perhaps angry, the child sought guidance from their parents.

Luke Bryan’s alleged response — telling the child they were permitted to punch a persistent bully — is what made the story go viral. It’s an emphatic parental message: don’t stand for physical or emotional harm; defend yourself.

It’s worth underscoring that the conversation around the details has been heated and fragmentary, and statements attributed to public figures can be amplified and reframed in social media. Regardless of the precise wording or context, the core tension is real: how far should parents go to protect children from bullying while modeling lawful, constructive behavior?

Why the response resonated — and alarmed — so widely

There are several reasons this moment cut through the usual celebrity news cycle:

- Parental instinct vs. public example. Parents generally feel a fierce, instinctive need to protect their children. Celebrities’ reactions are amplified, however, because they become public role models. A private household rule becomes a message received by millions. For some viewers, Bryan’s blunt directive felt like an honest expression of that instinct. For others, making violence the first-line solution felt irresponsible.

- Bullying is a universal fear. Many people have experienced bullying, either as victims or as the parents of victims. The idea of a child returning injured triggers emotional protective responses. That raw emotion makes a tough, paternal edict seem understandable, even righteous.

- The realities of school discipline and safety. Parents often feel frustrated with school systems they perceive as slow to act or ineffective at stopping repeat bullying. That dissatisfaction can make physical retaliation look tempting to some families, especially after a perceived institutional failure.

- Legal and moral implications. Advocating or instructing a child to physically assault another child brings immediate concerns about legal liability and moral modeling. Schools, police, and courts do not treat “they bullied me first” as an automatic justification for violence. Many worry that encouraging kids to hit back escalates risk rather than reduces it.

The legal and practical consequences of encouraging violence

It’s important to be clear-eyed about the risks of instructing a child to resort to bodily harm, even in a defensive context.

- Potential criminal charges: In many jurisdictions, physical assault — even between minors — can result in police involvement. If a child punches another child and causes injury, the parents and children could face criminal investigations, juvenile consequences, or civil liability for damages.

- School disciplinary action: Schools have codes of conduct that typically prohibit fighting. A child who responds with a punch may face suspension, expulsion, or other disciplinary measures even if they were initially provoked.

- Escalation and safety concerns: Physical retaliation can escalate conflicts and lead to more serious harm. A scuffle involving multiple children could have unpredictable outcomes.

- Modeling aggressive conflict resolution: Children learn behavior from adults. When parents endorse violence as a solution, they risk teaching kids that force is a primary way to solve disagreements, which can affect future relationships, schooling, and employment.

Those practical realities are why many child psychologists, school administrators, and legal advisors counsel against encouraging reciprocal violence. They urge parents to prioritize reporting, documentation, and safe de-escalation tactics.

Alternatives parents can try (that reduce harm and risk)

If your child is being bullied, the instinct to “make it stop now” is natural. But there are safer, legally sound, and often more effective steps parents can take that don’t involve instructing physical retaliation:

- Document everything. Keep a written record of incidents: dates, times, locations, witnesses, what was said and done, and any injuries. Photographs of injuries and copies of messages help build an objective case.

- Report to the school. Follow the school’s bullying-reporting procedures and demand a response. Escalate to district administrators if the situation isn’t addressed.

- Request a safety plan. Schools can implement supervised transitions, changes to seating, or monitored areas to reduce contact between students.

- Involve counselors and mediators. Restorative justice programs or mediated conversations — when facilitated by professionals — can resolve underlying conflicts and hold the bully accountable while reducing retaliation.

- Teach assertive but nonviolent responses. Role-play ways a child can respond, such as removing themselves from the situation, loudly requesting adults’ help, or calling for assistance from a teacher.

- Build social supports. Encourage friendships and supervised activities where the child feels safe and empowered.

- Engage law enforcement when necessary. If threats are serious or assault is repeated and the school fails to act, contacting local authorities may be appropriate.

These alternatives protect the victim and reduce the chance of legal or disciplinary backlash.

The emotional side: Why parents sometimes want retaliation

Even when the logic favors nonviolence, the emotional pull toward retribution is real. Parents can become consumed by anger, shame, or a feeling of helplessness when their child is harmed. Saying “you can hit them” is a symbolic restoration of agency: it’s a way of conveying to a child that they are not powerless.

Acknowledging those feelings is valid, but acting on them through violent instruction is seldom the wisest route. A healthier response channels that fierce protectiveness into advocacy: documenting the harm, mobilizing support, and pursuing justice through appropriate channels.

What experts often recommend when a child is injured by bullying

Child development specialists and school safety experts typically recommend a measured, multi-step response that preserves safety and dignity:

- Address the injury first. Seek medical attention if needed and treat physical wounds. The child’s physical and emotional safety is the priority.

- Listen and validate. Let the child tell their story without judgment. Validation reduces shame and helps build trust.

- Make a plan together. Discuss steps the child feels comfortable with — who to report to, how to avoid unsafe situations, and when to involve adults.

- Empower but don’t arm. Teach skills for de-escalation, assertive communication, and executive help-seeking. Reinforce that asking for adult help isn’t tattling; it’s staying safe.

- Hold the institution accountable. Press the school for consistent enforcement of anti-bullying policies and for the safety measures that protect all students.

This balanced strategy seeks safety, accountability, and long-term resilience.

Where public figures fit into the conversation

When celebrities voice opinions about parenting and discipline, they influence public discourse. Fans may adopt their stances; critics may call them out. A high-profile figure advocating for violent retaliation, even as a protective measure, will inevitably spark controversy and calls for nuance.

A constructive public role for celebrities — who are heard widely — is to raise awareness of the seriousness of bullying while also modeling lawful, nonviolent solutions: urging stronger school policies, funding counseling programs, and advocating for community resources.

The takeaway: Protect your child — but choose the path that keeps them safest

Luke Bryan’s alleged statement captures a raw, unfiltered parental reaction many people understand: a burning desire to protect a child who’s been hurt. It’s an emotional moment that underscores just how personal and painful bullying can be.

At the same time, encouraging a child to respond with a punch is fraught with practical, legal, and moral peril. It risks escalation, discipline, and modeling aggression as acceptable conflict resolution.

Parents must walk a difficult line: they must be fierce advocates and protectors for their children while also teaching safety, self-control, and lawful responses. When a child comes home injured, immediate steps — medical attention, documentation, and reporting — should come first. Emotional support and empowerment should follow. And when systems fail, parents should escalate to district administrators, community organizations, or legal counsel rather than encouraging physical retaliation.

If this story has one constructive result, it’s that it reignites a vital conversation about bullying — how it shatters trust, how schools and communities must respond, and how parents can bolster their children without sowing further harm. Protecting our kids doesn’t mean teaching them to be violent; it means ensuring they’re safe, believed, and equipped to navigate conflict with dignity and support.